From Above and Below to Side By Side

An excerpt from Linda Quiquivix's new book, Palestine 1492: A Report Back

Note:

This missive has an excerpt from my friend Quiqui’s new book, Palestine 1492: A Report Back. It contains some of the brilliant analysis I’ve come to expect in Quiqui’s work, and I’m glad to be able to share it with you. I highly recommend you purchase the book to get the full analysis, interwoven with stories from her own life and experiences in Palestine and Chiapas.

In this eve of another election in which two parties, neither of which are accountable to the people, vie for power, in which we have the choice between a man who has openly discussed using the military to go after those he calls “the enemy within,”1 or another candidate continues to support genocide in Gaza and escalation of war in Lebanon and intensifying border imperialism,2 there remains no lesser evil choice. Quiqui’s words remind us that we do not face new struggles, only new masks on old struggles. Her book reminds us that the only way out is through–side by side.

Here is more about the book from the publisher, Wild Ox Books:

Palestine 1492 is a report back of what I see from 500 years of the struggle for life in words, maps, and images in the seven cardinal directions and in the spiral that is time.

In Maya geography, there is east, west, south, and north, and there is also earth and sky. In the middle there is you, a meeting place between the physical, spiritual, emotional, and mental that together make up the social, a meeting place between earth and sky.

East, the physical, begins this report back by orienting us in a corner of Mother Earth still holding a stubborn insistence on life: Palestine.

West, the spiritual, helps diagnose an illness of a wounded, imbalanced, and dangerous world imposed globally since 1492.

In the South, the emotional, Chiapas nourishes our courage from below in a time of World Wars and global rebellions.

In the North, the mental, we flip the world on its head but not to remain, to help plan our common escape.

Throughout, I share conclusions Palestinians, Zapatistas, Panthers, and jaguars have taught me along this journey: that this world itself is unethical, and that changing it is difficult, even impossible. If after reading you also believe this to be true, may we dismantle this world together and help build a new one from below and in common, together and side by side.

An excerpt from Palestine: A Report Back, pages 278, 294-297.

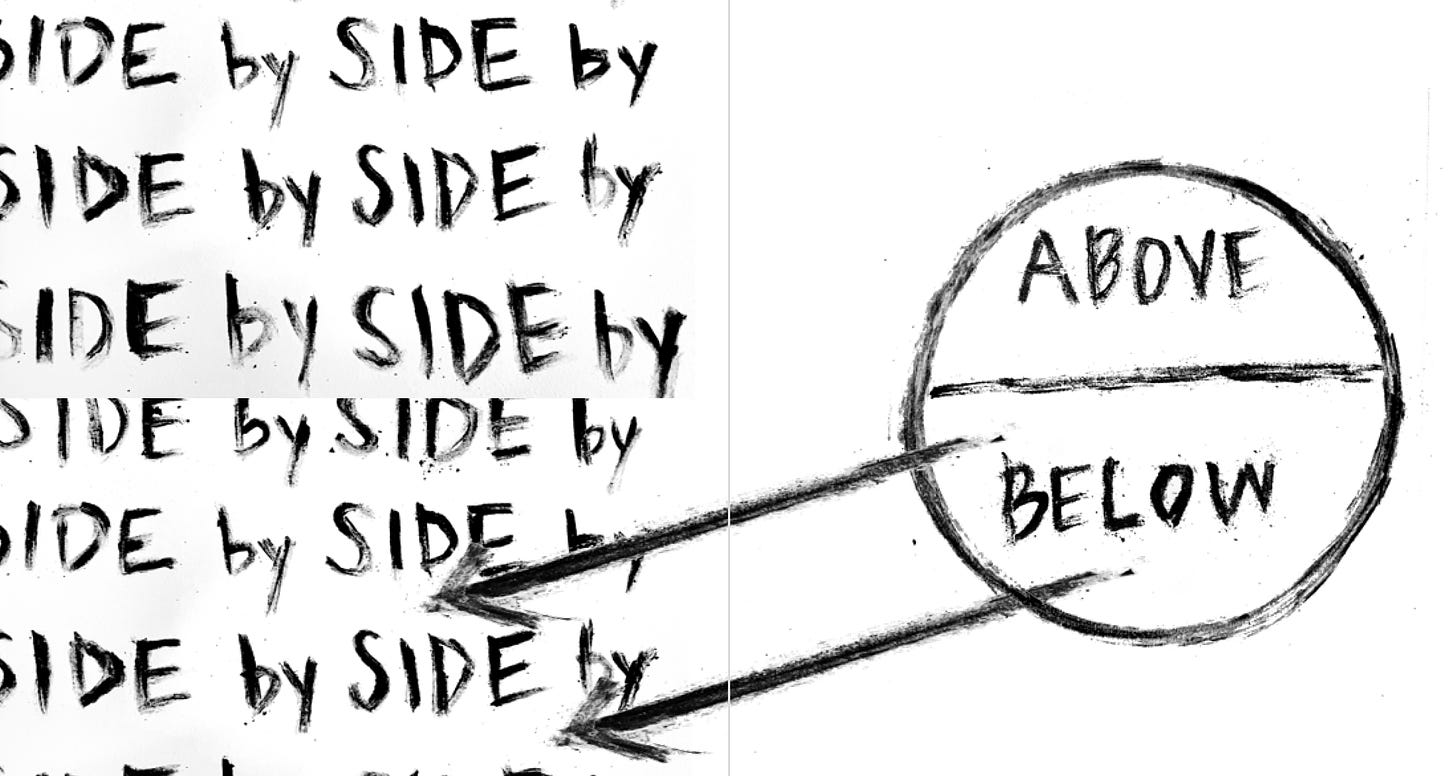

When I use the word “left” in “from below and to the left” I use it to make a distinction between it and “from below and to the right,” the tragic dominant posture of the below as I have experienced the below. To be below is to be crushed by the above. To be below and to the right is to wish to become the above, to become like the masters, to impose one’s world on and crush the other belows. To be to the right is to not respect difference. There exist Christianities from below and to the right. There exist Judaisms, Islams, Buddhisms, Hinduisms, Marxisms, Anarchisms from below and to the right, as well as from above and to the right and from above and to the left. If not the word “left,” is there another word we can use to convoke and to affirm an ethical posture against injustice, a vision of sharing the world with all our difference?

I can be convinced to give up on the word “left,” but not without insisting much of the below doesn’t want to escape together to create the world anew. So, what words do we use to talk about that part, too, about our common vision and not just talk about the below?

A world anew requires a brave answer to the question, Could it be another way? What will it take for the answer to be Yes by each of us, and in our own geographies, in our own calendars, and our own ways? What will it take for us to keep finding each other along the way? What will it take for us to really mean it, where we’re not simply using words, co-opting words, where we’re not replicating the same world of above vs below?

The first time I heard about sharing the world side by side as an alternative to above vs below, I was listening to Sylvia Marcos speak in Chiapas for the first time. The Mexican intellectual was quoting the Palestinians on the challenge of hope. The day was January 1, 2013, the 19th anniversary of the Zapatista uprising. We were gathered with a thousand others from around the world at the Indigenous Center for Integral Capacitation (CIDECI) near San Cristóbal de las Casas, at its Third International Seminar of Analysis and Reflection, “Planet Earth: Anti-Systemic Movements.”

Sylvia was speaking alongside autonomous movements from Mexico and around the world, from the Purépecha peoples in Cherán to the Mapuche peoples in Chile. She was joined by other movement elders, including artist Emory Douglas of the Black Panther Party; the late Zapatista intellectual Pablo González Casanova; and the late architect and militant intellectual Jean Robert, Sylvia’s life partner.

When Sylvia spoke that day, she described the march of over 40,000 Maya Zapatista men, women, and children throughout Chiapas that had just taken place on the 21st of December of 2012, the end of the Maya long count. The Zapatistas had marched quietly that day with no single leader, with all of them leaders. Each stepping up on a stage they built and transported with them for the occasion, and stepping down off stage just as quickly, juntos y a la par, together and side by side. Sylvia emphasized that part, “together and side by side.” I soon learned it is the focus of her work on Mesoamerican philosophies and worldviews.

Together and side by side is a Zapatista women’s demand, philosophy, and practice of walking alongside the Zapatista men in struggle, in a complementarity of difference rather than in a competition. That is, they do something very other than repeat the logic and practice inherent to domination, inherent to patriarchy. When Sylvia ended her offering that evening with, “We have to expect to be prisoners of hope, like the Palestinians say,” I knew I needed to introduce myself. I was in attendance as a listener seeking to weave more between Chiapas and Palestine, seeking to organize a Palestinian delegation to Zapatista territory. I had just encountered the right person. When I shared with Sylvia my task, she responded, “I am Palestinian. My grandparents were from Bethlehem.” We embraced.

The next year in her home, we gathered with a Palestinian delegation of women, all of us having returned from week-long stays in Zapatista territory as students in their Escuelita, their Little School. We exchanged our experiences and remarked on the weavings between Chiapas and Palestine, present in different degrees in both geographies.

Each Little School student had received four textbooks: Autonomous Government I; Autonomous Government II, Autonomous Resistance; and Women’s Participation. We were given time to read them while visiting the Zapatistas’ autonomous clinics, schools, food gardens, cooperatives, and justice systems, and while sharing back with them how we were organizing where we lived, what our struggles looked like. Sylvia shared from her Little School experience by outlining the ways the Zapatista Women’s Revolutionary Law of 1993 was being lived in the present, as detailed in the textbook Women’s Participation. She was writing an essay pulling out the philosophical foundations of the Zapatista women’s struggle against patriarchy and emphasized a fluid dualism between men and women, not a binary dualism of Western feminism that responds to patriarchy by reversing the positions of domination, that responds by placing women as superior to men in struggle. The Zapatista women insist that their struggle is to live together and side by side, women and men, not above vs below.

I offered to translate her essay, published that year in 2014 as “The Zapatista Women’s Revolutionary Law as it is lived today,”3 and in the process, I received from Sylvia some conceptual curanderismo, some conceptual healing. She helped me shake off the notion that all dualisms were bad, that all dualisms were binary, that all differences were in competition. She spoke of worlds of complimentary opposites and of fluidity in between.

Sylvia’s work intervenes against Western approaches to feminist justice that focus on switching the positions of domination between men and women, and on making demands for sameness between genders, for women to become oppressors like the men under patriarchy. Her writings instead emphasize the Mesoamerican worldview of difference existing “together and side by side” and the Zapatista women’s practice of walking alongside Zapatista men in struggle while being “the women that we are,” an insistence on difference, a complementarity of difference, not a binary competition toward a standard, toward sameness.

The call to respect difference rather than to tolerate difference was still new to me. Sylvia pointed me to another Zapatista phrase to help me shake it off: “We are equal because we are different.” I sat with that one, thinking about the definition of equality I had previously been taught: citizenship, and that to attain citizenship, several boxes had to be checked off, meaning a standard had to be met to attain equality, and that once a standard for equality was introduced, inequality was at the same time introduced.

If we begin with “We are equal because we are different,” then rather than being weak because of our differences, we are strong because of our differences, not in spite of them. When I asked Sylvia from where this wisdom came, she simply replied “It’s in nature.” Wisdom is observed all the time in nature.

Gerald Horne reminds us that American fascism is not new, but that it has historically only been deployed against certain groups: https://www.peacelandbread.org/post/what-american-fascism-has-already-looked-like

See the work of Harsha Walia, especially Border and Rule. https://www.thenation.com/article/culture/pulling-down-the-worlds-walls-a-conversation-with-harsha-walia/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CThe%20border%2C%E2%80%9D%20as%20author%20Harsha%20Walia%20puts%20it,hierarchical%20social%20ordering%2C%20labor%20control%2C%20and%20xenophobic%20nationalism.%E2%80%9D

Sylvia Marcos “The Zapatista Women’s Revolutionary Law as it is lived today,” openDemocracy ( July 2014)