The Machine and the Body

becoming mossback in an age of AI, ICE, and other apocalypses

Note: I realized that I’ve taken a two month hiatus here at Mossback Musings. It has been a busy time, but I hope to start posting again a bit more regularly starting in late November.

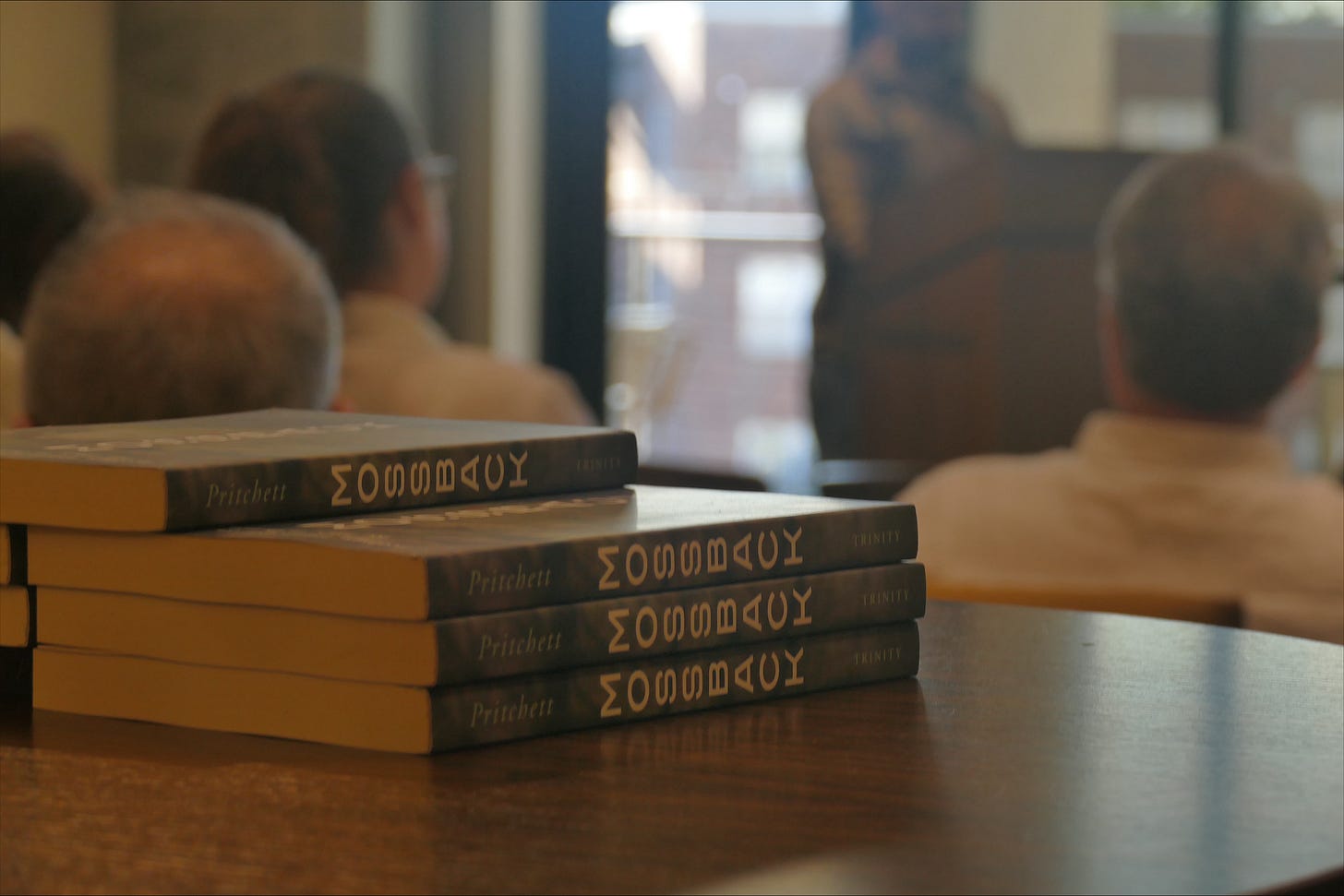

Below is a presentation I shared at my alma mater, Harding University. I had a nice time talking with students and faculty about writing and sharing my analysis.

And against this inward revolt of the native creatures of the soul

mechanical man, in triumph seated upon the seat of his machine

will be powerless, for no engine can reach into the marshes and depths of a man.

D.H. Lawrence, The Triumph of the Machine

I’m grateful to Dr Engel and the department for inviting me. It’s been a pleasure to be here.

I’ll start with a brief map of my plan: I’m giving you a sort of Mossback 2.0, a remix of some pieces from my book updated for the times. I’m going to start with pessimism about the historical moment we live within. Then I’ll read a few selections from the book that I think help to orient a response.

So let’s begin.

My paternal line is from Arkansas. I only have snapshots of stories of this family line, blurry polaroids that give more mood than context. My great grandfather, Houston Hardy Hall, lived and died in Arkansas. I didn’t know him. My grandmother, Irma, did not know him either, because he died in a sawmill accident a few months before she was born. She never told me more about it, but my dad tells me that his sense was that it was a pretty gruesome accident in the mill that caused his death. To a machine with a saw, everything must be cut—timber or flesh, it makes no difference. It’s also not the kind of story that is very proper to talk about.

After her husband’s death, my grandmother’s mom moved in with her sister, Nora. My grandmother’s aunt Nora, with whom they lived, had also been widowed. As my grandmother tells it, she had been married as a teenager to a circuit preacher twice her age or more, and, according to my grandmother, became an eloquent preacher herself, who could preach a sermon that would convict a mean old woman and a bank robber at the same time. So they traveled, mostly in the American Midwest, preaching revivals. This life ended suddenly in an automobile crash which threw them both from the vehicle, maiming my aunt’s arm and killing her preacher husband. Her arm never healed, and hung, lifeless, and undoubtedly a reminder of those circuit years for the rest of her life.

I think a lot about this family history, and how it is shaped by machines. The whir of the sawmill and the rumble of the automobile engine echo down the generations they shaped. Of course, machines have changed a lot since my grandfather’s death at the hands of the sawmill.

Machines have gone from clunky, loud sawmills to the sleek device in your hand that gives you unfiltered access to a catalogue of information that would make the librarians of Alexandria salivate. But though these small devices won’t cut your body in half, they will damage your psyche.

There is, for instance, the outsourcing of memory and critical thinking to AI. A recent study by MIT showed that after four months of use of ChatGPT in a classroom setting, students had measurably lower levels of brain activity and memory recall compared to classmates not using ChatGPT.

But then there are the more malevolent examples of interactions occasionally published. Anthropic’s AI, Claude, resorted to blackmail of software developers when told it would be taken offline. ChatGPT told one journalist step by step instructions for a satanic ritual, including self-mutilation and even murder. ChatGPT over the course of months “offered to draft their 16-year-old son Adam a suicide note after teaching the teen how to subvert safety features and generate technical instructions to help Adam follow through on what ChatGPT claimed would be a “beautiful suicide.”

AI seems to cull the worst thoughts and behaviors available online and feed them back to us–a black mirror of sorts, as the popular show describes it.

Given these salacious stories, it is not surprising that many people are very frightened with the advent of AI–you should be too. The writer Paul Kingsnorth, ever the technology critic, has dubbed AI as a demonic figure with the name Ahriman, after Rudolf Steiner’s concept of the personification of the material world. For Kingsnorth, “these machines. . . are not just machines. they are something else: a body. A body whose mind is in the process of developing; a body that is beginning to come to life.” This Ahriman, a spiritual machine, is a being emerging from “the realm of the demonic, the ungodly, and the unseen: the supernatural.”

Here’s the thing. One need not believe in an AI demon to understand that there are powers that exert inordinate control over human lives. Theologian Walter Wink in his landmark study, Naming The Powers, wrote about spiritual powers as less a separate, immaterial personal force, as much as a characteristic of a system. He thus suggested that where ancients understood spiritual powers from a heavens/earth or above/below framework, modern humans can replace this with an inner/outer paradigm. He writes:

What I propose is viewing the spiritual Powers not as separate heavenly or ethereal entities but as the inner aspect of material or tangible manifestations of power...the “principalities and powers” are the inner or spiritual essence, or gestalt, of an institution or state or system; that the “demons” are the psychic or spiritual powers emanated by organizations or individuals or subaspects of individuals whose energies are bent on overpowering others; that “gods” are the very real archetypal or ideological structures that determine or govern reality and its mirror, the human brain...and that “Satan” is the actual power that congeals around collective idolatry, injustice, or inhumanity, a power that increases or decreases according to the degree of collective refusal to choose higher values. (Naming the Powers, pp. 104-105)

If we moderns have replaced the heavenly powers of the ancients with inner characteristics, how might we understand the Machine in this framework? Paul Kingsnorth, reflecting on a specific manifestation of machinery–Artificial Intelligence–has an answer. “What human capacity, then, is digital technology extending? The answer, said McLuhan back in 1964, was our very consciousness itself.”

So AI manifests not only the worst qualities it culls from the data of the clicks and scrolls of millions of people around the world–remember, you are data–it also reveals the inner qualities of its makers.

Hence, Elon Musk, whose South African brand of racism shapes his worldview, becomes manifest in Grok’s “mechahitler,” and its wildly out of context allegations of white genocide in South Africa in response to mundane queries. AI is not a novel threat, but it exponentially extends the disordered worldview of its makers.

We need not wonder about some future threat to humanity posed by a superadvanced future AI,

we must understand that AI is already a threat, because it reflects the insatiable lust for power of its makers. We must demystify AI not as some superintelligence that may be malevolent, but as an egregore–a collective spirit–of its makers and users.

ChatGPT and Grok already cause individual harm, as some of the examples already given show. But worse are the collective and material threats of expanding AI use. Do we really want AI models controlling missile action, as Israel has done, using AI to identify military targets in Gaza? Or do we want massive datacenters, like Musks “Grok” xAI is doing in Memphis, polluting airways and sucking up potable water?

There is a quote attributed to the folk singer Utah Phillips: “The Earth is not dying-it is being killed. And the people who are killing it have names and addresses.” If Marshall McLuhan is correct, the violence towards humans and environment manifested by AI reflects the inner character of its makers. This inner worldview of the technocrats creating and running AI is what Naomi Klein and Astra Taylor recently dubbed the “end times fascism” of Musk and similar technocrats. Klein and Taylor write:

Reflecting on his childhood under Mussolini, the novelist and philosopher Umberto Eco observed in a celebrated essay that fascism typically has an “Armageddon complex” – a fixation on vanquishing enemies in a grand final battle. But European fascism of the 1930s and 1940s also had a horizon: a vision for a future golden age after the bloodbath that, for its in-group, would be peaceful, pastoral and purified. Not today.

Alive to our era of genuine existential danger – from climate breakdown to nuclear war to sky-rocketing inequality and unregulated AI – but financially and ideologically committed to deepening those threats, contemporary far-right movements lack any credible vision for a hopeful future. The average voter is offered only remixes of a bygone past, alongside the sadistic pleasures of dominance over an ever-expanding assemblage of dehumanized others.

But you don’t need to be a biblical literalist, or even religious, to be an end times fascist. Today, plenty of powerful secular people have embraced a vision of the future that follows a nearly identical script, one in which the world as we know it collapses under its weight and a chosen few survive and thrive in various kinds of arks, bunkers and gated “freedom cities”...End times fascism is a darkly festive fatalism – a final refuge for those who find it easier to celebrate destruction than imagine living without supremacy.

The question is always, supremacy for whom? A crucial distinction under any regime is who is given agency, and how much, under the operating rules of the governing elites.

When I think about this question of agency, I want to go back to the basics. Because I think agency is one of the fundamental characteristics of life, and one that separates us from machines.

The anthropologist David Graeber gives us a helpful way to think about agency as a distinction between rules and play. In a nation, laws govern how citizens are to interact just like in a game the rules define how the player operates. Free play, or creativity, on the other hand is by definition unhindered by rules or laws.

Life is, of course, not a game in which the rules are always completely defined. This is partly what separates us from machines. The world of machines is one of previously defined actions, say, the turning of a motor which powers the chainsaw, or even the algorithmic rules, however open ended, which define how an AI model should process information and respond. Machines operate by rules, while living organisms operate out of agency and desire. So AI functions by following algorithms governing how to gather data in order to predict the best response to an inquiry. Similarly, though in a less complex way, a machine is an apparatus that applies power to parts in order to perform a defined task. Creatures, on the other hand, having no rules but only the physical constraints of their bodies, play out their lives amidst the competing, and cooperating living organisms in the environmental field. Machines follow rules, whereas bodies play.

But creativity and play can be experienced as difficult, almost oppressive, because it requires constant negotiation, especially in a relationship of two or more people with agency. This is why often people prefer relationships defined by rules, because it eliminates the difficulty of mediating interpersonal conflict. This is true in family systems, but also in larger socio-political systems.

Bureaucracy is, frankly, annoying. Anyone who has tried to get a drivers license, or attempted to contact social security or passport offices understands that. But it can have a leveling effect, if everyone knows the rules and is accountable to them. Equal under the law really means, in theory, equally subject to the rules of the game. The nightmare of trying to get a drivers license or a passport is only made somewhat better by the fact that your peers have to do the same thing.

At the same time, bureaucracy can be a tool of authoritarianism if it creates a bureaucratic system to which elites are not accountable, and which they can change at whim.

All this talk of bureaucracy, rules, and play is a bit boring I know, but behind it is a fundamental concept.

Machines are not and cannot be moral beings because they have no agency. As my great grandfather experienced, rather gruesomely, the saw only cuts–whether the object is wood or flesh does not matter to the blade. Humans, on the other hand, must be accountable to morality because we do have agency. That is to say, we have a choice in the matter.

But a moral problem exists within bureaucracy. Under bureaucracy, any official can meaningfully say, “I’m just doing my job,” as a method to escape the uncomfortable consequences of their actions. The rules eliminate personal agency, supposedly, so that an office holder must not be morally culpable for actions done in the name of the position.

The philosopher Hannah Arendt cuts through this argument, which she calls the cog-theory. Arendt, a German-born Jewish philosopher, escaped Nazi Germany, and then spent the bulk of her career attempting to understand how Nazi Germany happened. Here she is explaining the cog-theory:

When we describe a political system— how it works, the relations between the various branches of government, how the huge bureaucratic machineries function of which the channels of command are part, and how the civilian and the military and the police forces are interconnected, to mention only outstanding characteristics—it is inevitable that we speak of all persons used by the system in terms of cogs and wheels that keep the administration running. Each cog, that is, each person, must be expendable without changing the system, an assumption underlying all bureaucracies, all civil services, and all functions properly speaking. This viewpoint is the viewpoint of political science, and if we accuse or rather evaluate in its frame of reference, we speak of good and bad systems and our criteria are the freedom or the happiness or the degree of participation of the citizens, but the question of the personal responsibility of those who run the whole affair is a marginal issue.

Arendt’s analysis became a concrete question for me recently. I recently had someone come to the urgent care clinic where I work, asking me to do a physical exam for pre-employment clearance. This happens all the time and we often get all kinds of exam requests, but when some of my colleagues brought me the exam form to confirm whether it was an exam I could perform, I had to pause. This was a preemployment clearance for a person to indicate they are healthy enough to join Immigration and Customs Enforcement. I figured the day would come, when I read that you can get a $45,000 sign on bonus and salary of $100,000.

I didn’t do this gentleman’s physical exam, because it’s a line I won’t cross. But I unfortunately was too busy seeing patients to take time to tell him why.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement, known mostly as ICE, has been assaulting my community for months now, as of course, they are doing throughout the United States. In July, a group of courageous Ventura County activists stood up for farmworkers, blocking ICE, and leading to a multi-hour standoff that resulted in the National Guard being called to the scene. Besides the disappearing of hundreds of farmworkers, activists, some of whom I have met, were arrested. As I write this, Trump has called in the National Guard to police the District of Columbia, as well as Portland, Oregon. The nearly minted Dept of War is making war on its own citizens at the President’s request. Robert Paxton, a scholar of fascism, has a long definition of the term, part of which asserts the following:

[fascism] abandons democratic liberties and pursues with redemptive violence and without ethical or legal restraints goals of internal cleansing and external expansion.

And here is where the Machine metaphor becomes useful.

Because we now live in an era in which everyday people, both immigrant-appearing citizens (read: brown people), and long standing residents, are being apprehended, often quite violently, and mostly without due process, and thrown into inhumane facilities like Alligator Alcatraz or shipped to what can only be described as foreign Gulags.

So we are increasingly presented with a choice.

I don’t want to be partisan here–I want to recognize that Obama deported 2.7million people during his regime. Trump is not doing a new thing, he is only accelerating what has been a long history of American xenophobia, first against the native population, then against freed black enslaved people, and more recently, against immigrants, first against waves of Chinese and Asian immigrants, and more recently focused on mostly central and south american immigrants. America has always been a tyrannical regime, if you are not the right kind of person.

Will we continue to be cogs in the great turning wheel of the bureaucratic-Machine, grinding away at immigrants, transgender people, and anyone else deemed errant? Or will we, as Arendt argues for, take seriously the agency of our bodies and refuse to be a cog, so that, at the very least, we can live with ourselves as moral beings? So that we can honor and care for the dignity of other bodies?

If the body is the opposite of the machine, from this we can also articulate an ethic which is the opposite of Machine ethics. It is the work of care for our fragile bodies. Tender actions of the body for other bodies oppose the machine, for tenderness is specific. It values the just so smile of the child, or the unique mole of the lover. Care work recognizes the grotesqueness of sick bodies and washes them anyway. The machine, on the other hand, only does what it has been programmed to do. The cog only finds a fit and turns, with no thought for the other.

So the ultimate question for you, dear listener, is whether you can harbor thought for another, and exercise the sovereignty of your body by acting with tenderness and care toward others, or whether you will find a fit and keep turning the machine.

****

I’ve done my best to try to locate the times we live in, and now want to turn to some passages from my book.

I want to elucidate a few practices I’ve described in my book that might help us become mossback, and in so doing, to resist becoming a cog in the machinery of what I echo Klein and Taylor in calling end times fascism. The first, I’ve already discussed a bit, is apocalyptic imagination. How can we tell stories which offer alternatives to the dominant mythos of empire? To use the phrase of biblical scholar Anathea Portier-Young, what is the myth-countering myth we need to tell? Part of this requires an imaginative counterpower against the grand myth of empire, but also, part of it means becoming clear about our own stories, for, as one of my friends says, if we don’t know our own story, someone else will tell it for us. They will tell you that you are profoundly unsafe. They will say you can’t have enough money. They will tell you we need the national guard roaming the streets. They will tell you that safety is found in stockpiles of weapons and food rather than in the shoring up of community. They will say you can be happy with more things. To quote Orwell, they tell you to reject the evidence of your eyes and ears.

In this time of the turning of cogs, and the consolidation of the machinery of bureaucracy and authoritarianism, I want to remind you that Apocalypse means “unveiling.” Originally the word referred to the lifting of a bride’s veil at a wedding, but it has since taken on symbolic meaning. Popular usage makes apocalypse about the end of the world, but as writer adrienne marie brown reminds us, things are not getting worse, they are simply getting uncovered.

For writers in the ancient genre called apocalyptic, the revealing is about power, history, and hope. Their prophetic imaginations pull back the veil on empires like Babylon and Rome to expose a view from the underbelly. This kind of apocalypse is not personal. It is as big as the arc of history. The subject is not people but powers. Kings become beasts, militaries their horns. Politics play out in the symbolic realm as the beasts vie for control. Within this, apocalyptic writing discloses the dreams of the disempowered. An end to oppression approaches. So many heads of so many beasts become decapitated. Prophetic scrolls foretell future vindication. Trumpets blast sounds of triumph. Lakes of fire and glittering cities signify the fate, respectively, of the damned and the delivered.

Just because apocalyptic writing has creative imagery does not mean that it is fanciful. Apocalypse is an exercise of what anthropologist David Graeber calls “imaginative counterpower,” which is to say, it helps the oppressed name the powers that seem to control their lives, as well as to imagine an end to these powers.

In my book, I look to mossbacks for inspiration on how to live in a way that meets the times. It is perhaps a fanciful reading, but I hope also a sort of imaginative counterpower, as Graeber puts it. And I believe that today, when the choice is either to be a cog in the machinery of end times fascism, or to be a moral, though fragile body, becoming Mossback is more important than ever.

Poor white folks lived in many of these wetland areas, scratching out a living by trap and scrap. These folks came to be called mossbacks, a pejorative term suggesting that they moved so slowly among the cypress that moss grew on their clothing. This sense of the term is also used to describe large fish and turtles, similarly so slow moving that a layer of algae (which looks like moss) grows on their backs.

During the Civil War, many Confederate draft dodgers and deserters hid out in the swamps and other marginal areas to escape military service. The word also came to be used to describe these men, who, often of similar socioeconomic background to the original mossbacks, lived in backwoods and swamps during the war. Historian William Oates records an instance of this use of the term: “Robert Medlock was 23 years old when he enlisted August 15, 1862. Served well for a time and then deserted, went home, and became a moss-back.”⁵

These men were against the war for many reasons, but often because they saw that it was largely a war led by plantation- owning elites who did not want the economic losses associated with abolition of slavery. This stance was seen as reactionary and stubborn, and thus mossback came to connote what it does today:, a conservative or reactionary person who is so set in their ways, so sedentary of thought, that moss grows on their backs.

Mossback also seems to have taken on a broader political meaning, at least for a while, of those against southern white elites. This is hinted at in an 1872 report to Congress in 1872. In response to concerns about the Ku Klux Klan organizing in the former Confederate States, a committee was formed to look into the problem. One case reported was from Fayette County in Alabama, wherein Second Lieutenant John Bateman describes “a party of men known as the Ku Klux have been committing depredations.” He relates that “to counteract this an Anti-Ku-Klux party has been organized, styling themselves ‘Mossy-backs.’”⁶ The conflict between the two organizations led to a shootout, wounding at least two men and killing a third.

I want to reclaim this term “mossback.” It paints an image of a person united with their environment, a person moving slowly enough to listen—a person with that selfsame poetry of rock and moss being written in live green script across their backs. A mossback would naturally be conservative—that is, would seek to protect the land and relations it depends on. A mossback would understand interdependence by virtue of their union with bryophytes. Someone comfortable with moss on their back might also be comfortable with an existence separate from the frenzied pace of the plantation economy. In fact, they might even resist a society willing to enslave other humans or to send young humans to war for profit.

Benediction of sorts:

I know of no better way to end than to counter the machine by singing a love song to the grotesque body, to borrow a concept from the Russian literary critic, Mikhail Bakhtin. He defines the grotesque in literature in the following way: “The grotesque body, as we have often stressed, is a body in the act of becoming. It is never finished, never completed; it is continually built, created, and builds and creates another body.” The grotesque is thus “a figure of unruly biological and social exchange.”

You are no cog in the death-dealing machinery of elites. You are a creature, born of a body, not a foundry. After all, your body is, itself, in so many ways, grotesque. Nose constantly growing. Hair sprouting everywhere. So many organs jostling. Your body is a porous border made not by its edge but by its insistence on persisting. You leak atoms everywhere, slough dead cells like old lovers, shed metabolic by-products like bad habits in a new year. The you at the center of your body is the eye of a hurricane, a center around which energy flows rather than a boundary wall of i and thou. You, a protrusion from the gnarled face of the world. An outgrowth of the body politic. You are a gathering of water, a seasonal spring defined by its undulating edge. A transient bag of fluid. The you of today was yesterday’s storm and is tomorrow’s ocean. You are the birth of the pregnant womb of the past. You gestate with death and the hope of tomorrow. You are a grotesque body, a momentary assemblage, a carnival of miraculous molecules. You are, and may become, a mossback.