My paternal line is from Arkansas. There are a lot of ways to describe the region, but I’ve heard someone say that if you were to drive from Little Rock to Memphis, the two most common words you would see on billboards are “Jesus” and “catfish.” That seems about the best and most succinct reflection of the place as one can find. If you were to drive through some of the smaller towns you’ll find entire buildings being swallowed up by creeping kudzu vines. I’ve stopped at some gas stations where roosters swing in cages from the ceiling. Arkansas has a history of people who are scrappy, resilient, and kind. But it also has a deep history of racism and extreme violence. In 1919, a white mob in Elaine, Arkansas, killed hundreds of black tenant farmers who were protesting their conditions. Cabot, Arkansas, close to where my ancestors lived, is still a hotbed of Klan activity. Of course, most of what I have described is recent history; Native Americans called the place home for much longer, though their history has been largely erased.

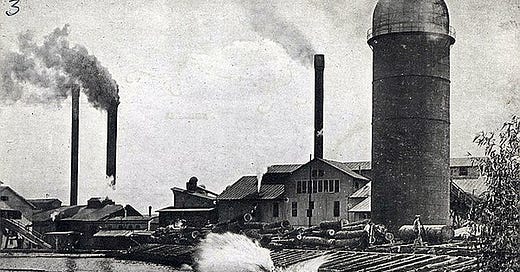

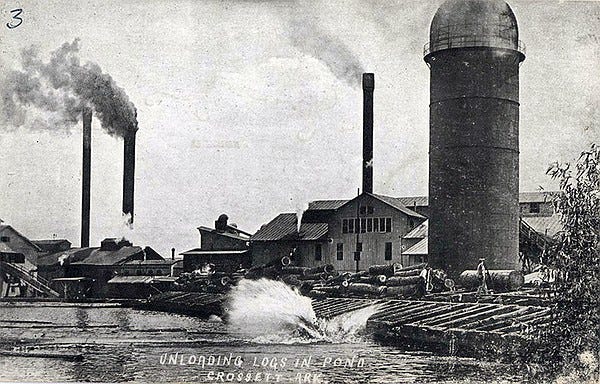

I only have snapshots of stories of my family line in Arkansas, blurry polaroids that give more mood than context. My great grandfather, Houston Hardy Hall, lived and died in Arkansas. I didn’t know him. My grandmother, Irma, did not know him either, because he died in a sawmill accident a few months before she was born. She didn’t tell me more about it, but my dad tells me that his sense was that it was a pretty gruesome accident in the mill that caused his death. To a machine with a saw, everything must be cut—timber or flesh, it makes no difference. It’s also not the kind of story that is very proper to talk about.

After his death, my grandmother lived with her sister Mary, a few years older, her newly widowed mother, Esther Hall, and her mother’s sister, Nora, in a one room cabin outside of Cabot, Arkansas. It was a hard life. They had to draw water from a well. There was no electricity in the cabin.

My grandmother’s aunt Nora, with whom they lived, had also been widowed. As my grandmother tells it, she had been married as a teenager to a circuit preacher twice her age or more, and, according to my grandmother, became a eloquent preacher herself, who could preach a sermon that would convict a mean old spinster and a bank robber at the same time. So they traveled, mostly in the American Midwest, preaching revivals. This life ended suddenly in an automobile accident, which threw them both from the vehicle, maiming my aunt’s arm and killing her preacher husband. Her arm never healed, so hung, lifeless, and undoubtedly a reminder of those circuit years for the rest of her life.

My great-grandmother Esther, my grandma Irma’s mother, remarried after a few years. Reading between the lines, I believe it was to get her girls out of the abject poverty in which they lived. Her new husband was a cruel man. No one has ever said that exactly, but whenever my grandmother talked about that time, she would not talk about him, and her eyes would darken. I don’t know if he abused her or only her mother, and I don’t know the extent of the abuse. But I do know that she got out of that house as soon as she could. She met my grandfather, who was staying at the YMCA where she worked as a desk clerk. He was over 14 years her senior, and she was still a teenager. But when he courted and soon proposed to her, she jumped at the chance.

I think a lot about this family history, and how it is shaped by machines. The whir of the sawmill and the rumble of the automobile engine echo down the generations they shaped. If not for the sawmill, perhaps grandma Irma would have grown up with a loving daddy. Perhaps her mother would not have married to escape poverty and perhaps Irma would not have had to escape an abusive household. Perhaps great aunt Nora would have two good arms and a preaching circuit.

So when a few years ago, Paul Kingsnorth started writing his substack series, The Tale of The Machine (now due to be published as a book, Against the Machine in Sept 2025), I was a primed and sympathetic audience.

……………

For over a decade, I’ve been following the work of Paul Kingsnorth. I read the Dark Mountain Project Manifesto, and was mesmerized by the forceful prose and poetic imagery, combined with an analysis of the environmental crisis which rang differently from any other discourse on the subject. His essays were always intellectually provocative, and contained toothy prose.

For that reason, Kingsnorth is a lauded writer. His first novel was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize. His essays and articles have been published in a variety of top notch magazines and journals, including The New Statesman, The Guardian, Granta, and Adbusters. The aspiring author, especially if they write in realm of environmental literature, would do well to pick up his words and pour over them.

Kingsnorth came to prominence writing about environmental issues, and his book, Confessions of a Recovering Environmentalist, made clear that he was ready to change the nature of the conversations about climate change and the environmental movement. By the time this book was published, he and Dougald Hine had already been changing the conversation with their publication, the Dark Mountain Journal. One of their theses in the Manifesto describes how they attempt to shape the popular dialogue on environmental collapse:

We reject the faith which holds that the converging crises of our times can be reduced to a set of ‘problems’ in need of technological or political ‘solutions’.

“No, there is no solution,” they insist.

While perhaps my analysis of the situation was not so darkly tinted, I shared much of the Kingsnorth’s critique of political or technological solutions due to the “anarchist squint” (to borrow a phrase from the late anthropologist James C Scott) that I bring to the many unfolding crises of our world.

A few notes about this and the forthcoming pieces I’ll be writing on the Machine series. What follows isn’t quite a review. His substack series, if I’ve gotten all the essays, is around 136,000 words. So it would be rather impossible to write an adequate review of that kind of volume that could have any specificity. I’ve instead focused on some threads that seem important to me to discuss, largely because I have various disagreements with them. And just to be clear, I’m basing my reading on his substack series, not his forthcoming book, which I do not have an advanced copy of. It’s possible he addresses some of my concerns in the book version.

It is probably the nature of humans to be most critical of people with whom we otherwise align, and I think this is certainly how I relate to Kingsnorth. His prose is characteristically sharp, and his argument against the forces that shape our individual and community lives and livelihoods is mostly salient to me. So the areas of agreement make the places of contrast more pronounced.

That said, his series clearly has had an impact. Many of the essays have hundreds of comments, and it has been popular enough to condense into a book. So this being the case, I think it is worth taking a look underneath the hood of this series.

In the rest of this first post, I’ll analyze the overall metaphor Paul uses of The Machine, with particular attention to the difficulty in what he attempts to do.

………………..

“One of the awful facts of our age is the evidence that it is stricken indeed, stricken to the very core of its being by the presence of the Unspeakable.” Thomas Merton wrote those words in 1965, but it could very well have been written in 2005, or 2025. There is a poetic truth in naming the system, or systems, that dominate our lives as at their very heart unspeakable, or unnameable. Merton goes on to describe this system as actually a no-thing, a void:

“It is the void that contradicts everything that is spoken even before the words are said; the void that gets into the language of public and official declarations at the very moment when they are pronounced, and makes them ring dead with the hollowness of the abyss. It is the void out of which Eichmann drew the punctilious exactitude of his obedience...”

The system is a void in the sense that it cannot be completely understood or circumscribed. But Merton hints at the multiple interlocking cogs of a system: politics, bureaucracy, and militarism collude to create the awfulness of the Holocaust as perhaps the most extreme example of this Unspeakable system.

What Merton calls the Unspeakable, Paul Kingsnorth has found a name for. He calls it The Machine, and has written thousands of words in his attempt to name it, understand it, and resist it.

In a way, Paul Kingsnorth has been writing against the machine for most of his career. His first book, Real England: The Battle Against the Bland, was a search for the dregs of real English culture lost in the wash of a “globoculture of sameness.” While he did not use the same terminology at the time, that book was the first of his attempts at rhetorical resistance against what he now calls “the Machine.”

Kingsnorth is not the only one who has taken up the mantle of critiquing technology and the ways it has negatively impacted human life. He stands in a long line of techno critics. I’ll summarize a few of them: Lewis Mumford, Jacques Ellul, Neil Postman, and Ivan Illich. The insights of Mumford, especially, as well as Ellul, form much of the foundation of Kingsnorth’s thesis. Postman adds some helpful clarity to the conversation, and Illich, brings a vaguely anarchist, but helpful lens to think about technology.

Lewis Mumford was an American writer who produced multiple books, many of which carried critiques of technology and its influence on human civilizations. For Mumford, technology is not completely malevolent. In fact, he utilizes the original Greek term techne, which encompasses not only capacity for complex machinery, but also deftness of artistic skill and how a culture prioritizes prowess in art as well as scientific aims. Mumford believed technology can serve human civilization. For instance, in his book Technics And Civilization, he distinguishes between polytechnic cultures, which utilize a variety of technologies, versus monotechnic ones, which overly rely upon one, which causes civilizational stagnation and fragility. He considers the American reliance on the automobile as an instance of monotechnics, and critiques how the automobile impacts American society by creating sprawling cities which are car-oriented rather than human centered.

Mumford’s two volume work, The Myth of the Machine, is a sprawling account of how technology has acquired mythic status. The entire work clocks in at over 800 pages, but is quite readable. Mumford describes the complex interweaving of machines and human culture as a Megamachine, and says that this “authoritarian kingdom” has joined with political power to render human life less meaningful. The problem with the Megamachine is that it undermines humans’ ability to live a full and spiritually satisfying life. Mumford locates the development of the Megamachine as starting with the pyramids of Egypt, and he notes that in the pyramids, we see that humans themselves become cogs in the wheel of a political-mechanical process subservient to this complex of the Megamachine. He finished the two volume set with a critique of what he sees as the contemporary Megamachine, which he calls the Pentagon of Power, in which military and industry create a five fold (pentagonal) combination of politics, power, publicity, productivity, and profit.

Jacques Ellul was a French philosopher who similarly critiqued technology. His assessment likewise relies on the idea of techne. His book, The Technological Society, is an english translation of his book, La Technique, in which Ellul enumerates an analysis of the implications of how technique, a concept in the same conceptual group as efficiency, has come to dominate humankind. He begins with “primitive activity of man,” which already involves technique. He notes that hunting, fishing, and textile making are simple techniques. Here, a sort of fatalism already develops in his reasoning. Because humans have always depended upon inventiveness, and eagerness to improve results, “Our modern worship of technique derives from man's

ancestral worship of the mysterious and marvelous character of his own handiwork.” Statements like this, as well as the way he articulates technique as nearly all encompassing, make it difficult to imagine any alternative.

One immediate problem is how complex his argument is, and how vague his idea of technique is within the text. After reading a few chapters, technique seems to include everything. Ellul seems to have realized this, and decided to clarify this for the reader in his preface. He defines technique in the following way in his preface to The Technological Society:

The term technique, as I use it, does not mean machines, technology, or this or that procedure for attaining an end. In our technological society, technique is the totality of methods rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency (for a given stage of development) in every field of human activity.

So for Ellul, La Technique means the logic and application of efficiency, at all costs, in all arenas of life. He believes then, that both machines (devices which perform a task, ), as well as technology (the application of science to practical output), represent by-products of technique.

Ellul elucidates seven characteristics of technique, nicely summarized by Samuel Matlack:

rationality (for example, systematization and standardization) and artificiality (subjugation and often the destruction of nature). The other five characteristics of technique are less widely discussed. They are automatism, which is the process of technical means asserting themselves according to mathematical standards of efficiency; self-augmentation, the process of technical advances multiplying at a growing rate and building on each other, while the number of technicians also increases; wholeness, the feature of all individual techniques and their various uses sharing a common essence; universalism, the fact that technique and technicians are spreading worldwide; and autonomy, the phenomenon of technique as a closed system, “a reality in itself … with its special laws and its own determinations.”

More recently, Neil Postman wrote a now classic book called Technopoly. Postman articulates three cultural approaches to technology, which might also be seen as stages. First, tool-using cultures use technology only to solve certain problems. These cultures can still have quite sophisticated machinery, but, as Postman sees it, their tools and technology do not have a central place in the worldview. So, for instance, in the Middle Ages, one can find wind mills and corn mills. In the same vein, Postman theorizes that the pyramids of Egypt represent a tool-using culture, because the pyramids, obviously the result of bureaucratic and technological sophistication, still reinforce the worldview of the culture rather than becoming central to it. However, Postman tells us that the technology of a tool-using culture can fundamentally change the culture. He offers Galileo’s telescope as one such example. This device, along with Galileo’s observations, challenged the idea that humanity was central to the cosmos. Postman says that the telescope, along with the clock and the printing press, so changed the culture that they led to what he calls technocracy, where tools “play a central role in the thought-world of the culture.” This insertion of technology into the worldview of a society, or technocracy, represents a second and more intensified stage. Finally, Postman describes technopoly, which is totalitarian technocracy, where no alternative to the techno-centric culture can be imagined. For instance, can anyone born after 1990 really imagine a world in which the internet does not exist, or can any gen Z person imagine a life without a smartphone?

There are some obvious problems with Postman’s framework. For instance, one could easily argue that the technology of fire had already fundamentally changed hominins' relationship with the world hundreds of thousands of years ago. Indeed, humans could not have covered nearly every habitat of the globe, especially the cold humid ones, without fire. We are, as James Scott notes in Against the Grain, a pyrocentric species just as much as the pyrophytic plants that depend on fire to reproduce and thrive. Fire occupies a central place in the ritual and mythology of most, if not all, cultures. Does this mean we have always been in a technopoly? The same could be argued with the way agricultural technology centrally changes a culture compared to hunting and gathering cultures. So his argument is a little myopic perhaps, in that he tends to focus on inventions and technologies in the last millennia.

Still, Postman’s delineation of the way tools impact a cultural world seems to me to be an important contribution, and somewhat less complex (and more readable) than Ellul’s erudite (but perhaps typical of continental philosophy) ideas of technique.

I’ll end this section with a discussion of one final member of the techno critic club. He is one of my favorites, in fact, Ivan Illich. His book, Tools for Conviviality spells out what is in my mind a helpful way of approaching tools and technology. Illich believes that some tools support conviviality, that is, “support the meaningful and responsible needs of fully awake people.” In this list he would include telephones (before the age of smartphones), printing presses, bicycles, and more. These support the togetherness and meaningfulness of social life. On the other hand, he writes, some tools and technologies are destructive no matter who uses them. In contrast to convivial tools, these tools have an end goal of efficiency, and are often only used by professionals. These tools increase dependency, and ultimately do not work for people, but rather increase their slavery to systems outside their control. He describes the predicament: “The evidence shows that, used for this purpose, machines enslave men. Neither a dictatorial proletariat nor a leisure mass can escape the dominion of constantly expanding industrial tools.” He would include under this rubric most forms of mass transportation, industrial mining, and specialized tools that are not accessible to the common person but rather depend upon a highly trained person to use the tool autonomously. While what defines a tool of conviviality is itself a concept which needs constant negotiation between people, I think his rubric offers a helpful way forward.

So Paul Kingsnorth’s Tale of the Machine series stands in a tradition of critiquing the role of technology and mechanics in our lives. And yet, despite his long arc of attempting to understand and articulate this thing that has occupied his imagination for so long, it seems he is not quite capable of truly defining it. Like Ellul’s “technique,” Kingsnorth’s Machine seems to encompass everything. It is numinous, everywhere. It is “a tendency within us, made concrete by power and circumstance, which coalesces in a huge agglomeration of power, control and ambition.” Kingsnorth references Lewis Mumford’s thesis that the pyramids of Egypt represent the first “megamachine,” which created its own mythos. He goes on to say that “Conquest and expansion are the essence of the Machine. If it could be said to have an ideology, it would be the breaking of bounds, the destruction of limits, the homogenisation of everything in its pursuit of its continued growth.” But the Machine is also not within us, it is an external, impersonal force. Kingsnorth takes his cue from Lewis Mumford to further describe the machine, noting, following Mumford, that it consists of “Those ‘depersonalised, collective organisations’ are the giant world-spanning corporations which now control most of our lives.”

If this all sounds a bit confusing, the reader should be assured that it is, and that what precisely the Machine is does not get much clearer through the series. The machine is a myth. It is within you. It is a deity. It is the corporations. It is a sovereign. It rises and falls with every civilization. Sure, Kingsnorth cites many examples of what he thinks the Machine is, but over time it seems like it might be easier to say what the machine isn’t than what it is. But he does not give us a via negativa of the Machine. Instead, we get rather long lists of whatsoever Kingsnorth doesn’t like. Global capitalism. The ideology of fascism and communism. Wokeness. Woke legions. The Great Awokening. [At times one might suspect they stumbled upon the transcript of a Fox News pundit]. Critical social justice. Definitely trans people. Even quite banal aspects of human life for Paul Kinsgnorth feed the Machine. Miniature golf. Chocolate bars. Having a pint with a friend. It starts to get fairly cynical.

On the one hand, the difficulty in describing The Machine is not entirely the fault of Kingsnorth. How does one articulate a force which one believes is so powerful as to include all the above issues, and more? I find the metaphor of the machine inadequate to describe what Kingsnorth (and I with him) identifies as having a sort of animacy. The system(s) that have so much control do seem to have a trans-historical, personal, and even adversarial aspect. How does one describe this with any sort of accuracy? Other Christian writers have acknowledged this a bit more by echoing Paul the Apostle’s terminology, Principalities or Powers. In this sense, I think Kingsnorth would do well to study Walter Wink’s analysis of what he calls “The Powers” or what William Stringfellow calls “The Principalities.” Perhaps it is best to follow Thomas Merton’s path and name the ineffable nature of this system within the words we use for it: The Unspeakable.

At the same time, while there is a numinous, personal quality of The Machine, or The Unspeakable, or whatever language you choose to use, it is also manifest in the very real decisions of people with a great amount of power over people’s lives. We know, for instance, that social media has been intentionally manipulated to increase its addictive potential. We also know that United Healthcare used faulty artificial intelligence to systematically deny healthcare to seniors and profit off their illness. So while the Machine is more than one person, we might also remember with the folk artist Utah Phillips that “the earth is not dying, it is being killed, and those who are killing it have names and addresses.” The face of the Machine is the face of billionaires and CEO’s. This is not to say that we don’t also have responsibility, but only to name the raw fact that the whims of people with inordinate wealth and political power have tremendous force in the world, and that power is mostly wielded for personal gain with evil results.

With the language of The Machine, there is a bit of sleight of hand going on. On the one hand, the way Paul Kingsnorth uses it, The Machine does have a sort of animus. It has personality. It has a purpose, and it feeds on growth. It is monstrous. At the same time, in the English language, a machine itself is generally understood as an inanimate object. It is not alive, and its purpose is only to perform a task for which it was created by its inventor. It is by definition impersonal. The sawmill did not intend to kill my great grandfather, he only got caught in its functioning. So making The Machine capitalized, a persona rather than a thing, collapses two ways of thinking about the problem of evil. Is The Machine only random—a historical and unfolding system in which we simply happen to be caught, as in a summer storm without an umbrella—or is the Machine truly a spirit with personality and intention to destroy? It does not have to be an either/or. The earthquake can kill just as the soldier can. But in naming this system “Machine” does complicate the picture by connoting the impersonal, while clearly including a kind of transcendent spirit animated by some sort of persona.

Ultimately, it is clear that Kingsnorth is attempting to describe something which he believes is at the heart of culture, at the level of values and cosmology. This is difficult to define because so often values and cosmologies are implicit rather than explicit, and can often be contradictory. What is more, they might vary by region or even family, and are subject to change over time. As much as a culture can be difficult to define, it can also be challenging to circumscribe. Since culture includes all the symbolic thought of a group of people (however one would define the group) it infinitely tangled.

I tend to be a bit allergic to the sort of systematic explanatory model Kingsnorth’s Machine series represents. I recognize the rhetorical value in attempting to thoroughly describe a metaphor one employs, but ultimately, I think the world is much more complex. The systems that seem to rule over our lives are not so easily defined by words. This isn't to say that many systems are not connected, it's just that I do not believe that their connections do not so simply fit into the rubric of one metaphor. It becomes so reductive that I don’t find it useful.

Kingsnorth’s vision, echoing that of Mumford, is that we jettison the cultural cosmology of the Machine which binds us to technology:

To liberate ourselves, steadily, one human soul at a time, we simply have to walk away from the Machine in our hearts and minds, as the Israelites of the Exodus walked away from its original master, Pharaoh. Or, as Mumford has it in the conclusion to the second volume of his masterwork:

For those of us who have thrown off the myth of the machine, the next move is ours: for the gates of the technocratic prison will open automatically, despite their rusty ancient hinges, as soon as we choose to walk out.

It is true that cosmologies are only grand stories, and that stories can be changed, or told differently. But there is no straight line from our present to a more creaturely future, just as there is no simple answer for how we got here.

My grandmother Irma, whose family I described in the introduction, died a short while ago. Even though we were only separated by one generation, there was a significant gulf between us in our experiences and assumptions–perhaps our very cosmologies–about the world. I wonder sometimes about what she would think about this talk of machines and technology. She was a pretty simple person, not prone to abstraction. For her, what mattered was what was in front of her. The dishes. Her ailing husband. The messes her grandkids made. I don’t think she had a critique of technology. But she didn’t really need one, because she had her hands to do work with. And those slender hands did a lot of caring for other people. If we are to accept as true what Kingsnorth along with Postman, Ellul, and Mumford articulate about the adverse role of tech in our lives, the question becomes how do we resist this enclosure of humanity within the bounds of machine thinking. This resistance is what Kingsnorth’s book is about, and I’ll discuss his own propositions for resistance in later essays. But when I think about what the alternative is to the Machine, it is the work of caring for other people. Technology can do a lot of things, but has thus far been a poor substitute for the kind of care work that is at the foundation of our lives, and at the same time is often so invisible. Machines cannot (yet) change a diaper, or sponge bathe the infirm. In short, technology cannot do what our hands can do. With her hands, my grandmother certainly used technology and machines, but she used them in a way that Ivan Illich would describe as in the service of conviviality. She used tools and machines to care for others. And I believe this work of care for others, with our dexterous, calloused hands, rather than any gears of a Machine, is what turns the world around.

“Technology can do a lot of things, but has thus far been a poor substitute for the kind of care work that is at the foundation of our lives, and at the same time is often so invisible.” I love how this ends in a simple call to do the good work our hands can do, too. Or that’s what I’m taking away. 🫶🏼